Economic contributions through entrepreneurship

Economic contributions through entrepreneurship

-

Immigrant entrepreneurship in Minnesota lags the rest of the nation. The state’s historically low unemployment, and high labor participation rates and job opportunities may be contributing factors, resulting in less entrepreneurship and startup activity. Minnesota’s comparatively younger immigrant population and immigrants’ higher education attainment levels are additional considerations.

-

Access to financial capital is a major barrier for immigrants eager to start a business.

-

As a primarily “homegrown” economy, rates of entrepreneurship in Minnesota are important to long-term economic success.

-

Building the systems that support immigrant entrepreneurs now is important to the development of the current and future economy.

Among the key characteristics of Minnesota’s economy are its industrial diversity and large number of homegrown enterprises, i.e. businesses that start, succeed and grow in the state. Fueling these characteristics are high-quality native-born and immigrant entrepreneurs and workers. The rate of entrepreneurship—whether native-born or immigrant—is modest relative to other states, but their businesses survive at a rate that’s among the highest. Workforce participation rates by native-born and immigrant Minnesotans alike are also high-ranking. Whether immigrants choose to be entrepreneurs and/or workers, they are contributing to the development and growth of the state’s economy. In previous sections, data presented their role as workers. Here data analyzes their role as entrepreneurs.

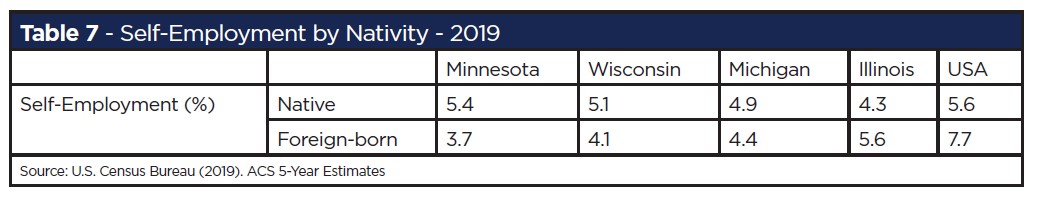

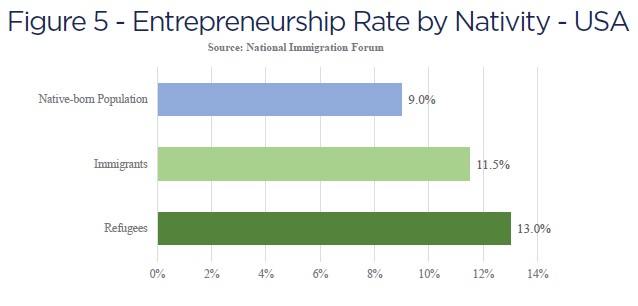

Entrepreneurial immigrants play an increasingly important role in the economy through job creation, innovation and GDP growth. In Minnesota, there were over 18,000 immigrant entrepreneurs as of 2018. Their firms employed 53,239 workers representing about 2% of the state’s total labor pool. Yet despite these positive numbers, Minnesota’s immigrant entrepreneurship rate lags the rest of the country. The U.S. Census Bureau collects data on self-employment rates throughout the country (self-employment is a useful proxy for entrepreneurship). Using Census Bureau estimates, Minnesota is on par with the nation’s self-employment rate among the native-born population, but significantly lags the foreign-born population self-employment rate. Nationally, immigrants have higher rates of self-employment (table 7), and when compared to peer states, Minnesota has a much larger difference between native- and foreign-born self-employment rates. According to the Census Bureau’s 2017 Annual Business Survey, the percentage of foreign-born business owners in Minnesota is on the low end when compared to its Midwestern peers and the nation. The National Immigration Forum found that immigrants throughout the U.S. are more likely to start a business than the native-born population. Refugees in the U.S. have a particular propensity for entrepreneurship. Specifically, figure 5 compares the national entrepreneurship rates among refugees, immigrants and native-born populations. As noted earlier, Minnesota has a particularly high number of resettled refugees which should correlate to a higher immigrant entrepreneurship level, but that does not appear to be the case.

National immigration trends further indicate that immigrant entrepreneurs tend not to follow the expected pattern of entrepreneurship rates, i.e. rising educational attainment. Instead, immigrants in the U.S. are actually more likely to start a business if they do not hold a bachelor’s degree. Among these foreign-born entrepreneurs with lower levels of educational attainment, construction, landscaping and food service are among the most popular industries to own a business.

Why is Minnesota different than other states? Some economists speculate that business startup activity may be low because new startups are both “need-based” and “opportunity-based.” Minnesota’s low unemployment rates and workforce shortage may mean immigrants are able to find good, stable employment that provides income and benefits for themselves and their families reducing the need to start their own businesses. As a “homegrown economy”, rates of entrepreneurship and startup activity matter for Minnesota’s long-term economic growth and success.

GreaterMSP, a nonprofit organization focused on economic development in the Twin Cities metro area, found that only 9,336 new establishments formed in 2019, which ranks at the bottom among our peer regions.

Additional data from the Kauffman Indicators of Entrepreneurship shows that only 0.18% of Minnesota’s population started a new business in 2019, down slightly from 2018. For comparison, the U.S. median has remained relatively close to 0.3% over the last decade. The opportunity share of new entrepreneurs is also very high, around 80%. This is the percent of new entrepreneurs who were not unemployed or looking for a job when they started their business, a distinction that provides further insight into why entrepreneurs may not be starting businesses in the state.

Recent research from the Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis explores other potential causes for this phenomenon. One explanation is the age of immigrants in Minnesota. The median age of the foreign-born population in Minnesota is over six years younger than the national foreign-born population. Looking at a more fine-tuned comparison within the Midwest, Minnesota’s peer states (Illinois, Michigan and Wisconsin) all have both a higher foreign-born self-employment rate and a higher foreign-born median age. State Demographer Susan Brower points out that younger immigrants “haven’t had time to age into business ownership.” It takes time for immigrants to accumulate capital and develop the business knowledge necessary to start a business.

The level of educational attainment among the foreign-born population is another possible reason. The rate of immigrants holding bachelor’s degrees or advanced degrees in Minnesota is higher than the national rate and most peer states. As previously discussed, immigrants are more likely to start a business when they have lower education levels. Minnesota’s foreign-born population is highly-educated, which is likely another contributing factor for the lower entrepreneurship rate.

After speaking with numerous immigrant business owners across Minnesota, a common theme emerged as a significant barrier to entrepreneurship: accessing financial capital. For most of the immigrants interviewed, this was the biggest challenge when starting their business.

Abdirizak Mahboub, a Somali-born entrepreneur, was able to secure financing to open a shopping center called Midtown Plaza in Willmar. “It was a challenge! I happened to get connected to a small bank in Willmar and I happened to know the owner.” He said his relationship with the owner allowed him to outline his business plan. He still had to provide a large down payment, something many immigrants don’t have. Eventually, he was able to access assistance from local economic development agencies.

New immigrants may lack the knowledge for navigating business financing as they compile a business plan. Entrepreneurs interviewed for this report were unaware of resources available to them until after they had started their businesses. Some started businesses out of their homes using resources from family and friends to get off the ground. A recent study of “current local government policies that aim at tapping into immigrants’ entrepreneurial potential” found that these policies address the information and language needs of budding immigrant entrepreneurs but are not aimed “at developing their business skills and facilitating their access to financial capital.” Both are critical to starting a business and pose a significant roadblock for immigrants to overcome.

Recent immigrants may also experience increased difficulty accessing capital because of their limited credit history. Community Development Financial Institutions (“CDFIs”) are a key resource for early financial assistance for immigrant business owners. CDFIs emerged from the first minority-owned banks in the 1880s that focused on providing financial services to low-income areas. Today, CDFIs are community organizations providing financial services to economically underserved markets. There are approximately 1,000 CDFIs nationwide, with 35 located in Minnesota, ranging from banks and credit unions to loan funds and venture capital providers. These community organizations link underserved populations, including aspiring immigrant entrepreneurs and business capital. Since 1996, Minnesota CDFIs have been awarded almost two billion dollars in loans from the Federal CDFI Fund through the U.S. Department of the Treasury. Awards have been issued to many CDFIs including the African Development Center in Minneapolis and the Immigrant Development Center in Moorhead.

Once an immigrant entrepreneur starts a business with the help of a community organization, they can then access traditional capital sources to grow and expand. Rick Beeson, Executive Vice President at Sunrise Banks, explained, “It’s hard to give money to startups” but CDFIs “prepare businesses for regular banking.” More traditional sources of financial services become available once a business establishes cash flow and projected sales growth. Connecting immigrant-owned businesses with community organizations that can access CDFI funds appears to be a key component of improving their viability and increasing entrepreneurship.

One successful example of this connection is K.C. Kye, the owner of K-Mama Sauce, a Columbia Heights-based Korean hot sauce company, launched in 2015. Because K.C. immigrated to the U.S. at a young age and had previous work experience in local government, he knew there were resources available to help start his business.

He connected with the Neighborhood Development Center (NDC) in St. Paul through a friend and fellow immigrant entrepreneur, tapping resources through the NDC and other nonprofits in the area. When asked his advice to increase the number of immigrant-owned businesses in Minnesota, K.C. said, “A personal connection or invitation from resources would be useful. Connecting immigrants to resources is tough. It needs to be done better, almost like hand-holding with immigrants to get them those resources. Many immigrants don’t know what’s available, so reach out to them directly to help.”

Marketing business resources to potential immigrant entrepreneurs is another potential way to improve access to capital. With time, as Minnesota’s immigrants age, assistance can be refined and scaled to potentially grow entrepreneurship within this population. In addition, the demographics of Minnesota’s native-born population suggest that there will be many employment and career opportunities for immigrants and native-born Minnesotans alike for the foreseeable future. Coupled with the younger age profile of Minnesota immigrants, there likely won’t be a significant increase in the rate of immigrant entrepreneurship any time soon. For Minnesota’s comparative age profile, see Appendix Table A5. Nonetheless, building the systems that support immigrant entrepreneurs is important to the development of the state’s current and future economy.

With support from The McKnight Foundation

![]()